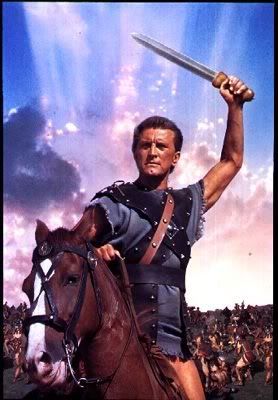

The basic storyline, that of rebelling slaves (starting with gladiators-in-training, but swelling from there), is fairly obviously treated by Dalton Trumbo and by the editing of the film itself, and therein lies one of the biggest problems. The rebellion is boring. We are treated to endless montages of poor faces in the crowd, spread liberally through the film whenever there is space for them, and after the first few the audience should be fairly well aware that slavery is bad and that their rebellion is just. What’s unfortunate to the “cause” is that the Roman “bad guys”—Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, and Peter Ustinov—are far more interesting and entertaining than the too-modern and rather pedestrian Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis. The best parts of the film are the conversations between Ustinov and Laughton (supposedly scripted by Ustinov himself) whose easygoing hedonism seems genial and harmless. Of course it isn’t, but it’s far more entertaining than Douglas preaching about rights with stilted language and heroically unrealistic lighting.

The basic storyline, that of rebelling slaves (starting with gladiators-in-training, but swelling from there), is fairly obviously treated by Dalton Trumbo and by the editing of the film itself, and therein lies one of the biggest problems. The rebellion is boring. We are treated to endless montages of poor faces in the crowd, spread liberally through the film whenever there is space for them, and after the first few the audience should be fairly well aware that slavery is bad and that their rebellion is just. What’s unfortunate to the “cause” is that the Roman “bad guys”—Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, and Peter Ustinov—are far more interesting and entertaining than the too-modern and rather pedestrian Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis. The best parts of the film are the conversations between Ustinov and Laughton (supposedly scripted by Ustinov himself) whose easygoing hedonism seems genial and harmless. Of course it isn’t, but it’s far more entertaining than Douglas preaching about rights with stilted language and heroically unrealistic lighting.Likewise the subtleties of Olivier’s performance—scenes of which were famously cut out at the behest of the MPAA because they suggested bisexuality—are far more interesting than the straightforwardness of the Americans. While no one would argue about who ought to have won, there is a problem when the viewer cannot wait to leave the rebel camp and go back to decadent Rome. Though of course the attraction of the ambiguously villainous over the stolidly heroic is not isolated to this movie, and the work that focuses on a “social problem” (and it seems clear to me that Trumbo meant to evoke some time period more contemporary than ancient Rome) is often preachy and dull.

That said, aside from a few modernisms of speech and a dreadfully dated score, the film remains an enjoyable and thoughtful alternative to the big budget action films of the present to which it is related. Looking back, it definitely shows the strain between writer, director, studio, and censor, and is not quite as “tight” and efficient as perhaps it should be. For myself, all of that is entirely overshadowed by Olivier, Laughton and especially Ustinov, whom I fell in love with from his first scene. While this makes it a very enjoyable film, the fact I can so easily take the perverse view indicates that it does not achieve what it was supposed to, at least for this viewer, and if it is a masterpiece it is a decidedly flawed one.

No comments:

Post a Comment