By now, we're all used to the benevolent alien trope. The alien(s) come(s) to Earth, humans are suspicious, do human-type things like try to blow it/them up, and then we learn a valuable lesson about healing the world or at the very least something about friendship and loyalty. (There is, of course, the apathetic version: alien comes to Earth and is corrupted by our culture, but we'll leave that for another time.) Especially after the early 80s, when we seemed to be inundated by them. But in 1951, I can't imagine that a movie like The Day the Earth Stood Still came as anything but a surprise.

Coming shortly after World War II, in the midst of the Korean War, and in the early stages of the Cold War (not to mention the era of McCarthy/HUAC suspicion), The Day the Earth Stood Still showed a different future. The one that would happen if Mutually Assured Destruction were allowed to reach its logical fruition. The story seems familiar enough now that it's hardly a spoiler to say that in it, a man comes to Earth and tells humanity it's on the brink of destroying itself.

Looking back on it 58 years later, a few things strike me. The movie seems simplistic in its world view, both in terms of the dangers that beset humanity and the idea that all we need is to start talking again to ensure peace. It also seems “naive” (or blessedly optimistic, considering your view) about Mr. Carpenter's sudden appearance in the midst of the boarding house family and his easy association with little Bobby; Bobby's mother's boyfriend is jealous, but no one seems to suspect anything strange about a man who offers to watch a stranger's kid—that is, they don't suspect what we do now, watching it. Is that our problem, or theirs?

But what's saddest to me is the knowledge that this movie couldn't be made today. It wasn't, when the remake came out last year (which, for the record, I have not seen, though it has been described to me). One could argue that audiences are more sophisticated now, and in a sense we are—we demand more jargon and no longer accept “it's a powerful nuclear engine” as an explanation for anything, though modern films rarely say more despite their explanations and exposition. But most of this film involves a stranger coming to town, attempting to learn about its people, and talking while touring the D.C. sights. All the violence occurs off-screen. There's a chase that basically entails the army keeping tabs on the movements of a cab and reporting back to HQ. A strange man and a little boy talk about physics and Abe Lincoln.

The Day the Earth Stood Still is not my favorite film, but in this basic scenario, it is the film I want to see: the film about how a literal alien interacts with our culture and navigates his living situation. And then calls on his giant robot. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it, despite its “simplicity.” It doesn't rely on adrenaline, and it makes a clear, if apparently obvious, point. Of course, the film started out as a point looking for a story, but I still admire its compactness.

Finally, while I knew the story and the politics going in, I was surprised by the fact that the “message” is so violent. Humanity must change its ways and become peaceful—by threat of force. Which begs the question: is this stance hypocritical, or merely Klaatu's practical way of dealing with an unenlightened species who understands nothing more?

Read more!

Saturday, March 28, 2009

Sunday, March 22, 2009

Watchmen (2009)

I was not in that group of comic book readers blown away by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen in 1986. In fact, by the time I was reading comics and watching movies critically, the bitter, reflective mode of the book had already permeated the superhero ethos, and its revolutionary aspects had been re-integrated into the texts it rebelled against. Even the animated Batman of the early 90's, my own foundational text in this genre, wouldn't have existed without this attitude, even if on the surface it was the stuff of Saturday mornings. When I finally read it a few months ago, it seemed more shocking in its use of pink and bright green than its philosophy, and I suspected the impact had been diluted by everything that had come after, along with my own visual preferences.

I was not, however, prepared for the travesty director Zack Snyder made of it that I saw last night.

However ridiculous (and racist, and homophobic) I found Snyder's 300, most of what I objected to in the film was present in Frank Miller's comic. I didn't like how it looked, either, but shiny computer graphics and faster-than-the-eye-can-see fight sequence editing are something I live with nearly every time I see a modern Hollywood film, and I just sound more curmudgeonly and bitter every year. Watchmen had that, too, and I was prepared. What I was not prepared for was the sheer disconnectedness of the text and the presentation, which impressed itself upon me within minutes.

Is it a spoiler to say that the Zapruder film recreation nestled in the credits was one of the most tasteless things I have ever witnessed, JFK's assassination writ large upon an IMAX screen for the cheapest of shots at one of the main characters? The scene was presented with no more nor less fanfare than the recreation of the famous WWII photo of the sailor kissing the nurse, substituting Silhouette for the sailor (who we can see heading off another direction in the background). What's most astonishing to me is not so much the audacity of the decision as the filmmakers' apparent inability to see the difference between the two appropriations. Both have the same gleeful, detail-oriented “because we can” attitude about them, and even if our emotions are meant to be manipulated in slightly different directions, the intent of both is clearly to titillate.

This lack of thought permeates the entire film, from the soundtrack to the fight sequences. For a film that's about recreating a beloved comic in painstaking detail (when convenient or showy), it's astonishingly unaware of what the comic is about. One would hope, in other words, that the makers of a movie about the depravity of modern society would take some care not to directly contribute to same. Instead, we are simultaneously lectured about standing by and letting violence happen and shown endless slow-motion frames of compound fractures rendered in loving, hyper-real, computer-generated detail. It's pornography, and it's exactly the sort of thing Rorschach would be combating. I'm hardly holding him up as an example to be followed, and neither am I condemning pornography. But they don't belong together, and what is more, I cannot sense the tiniest bit of intelligence behind the decisions that went into the making of this film. There's a fine line between demonstrating your point and subverting it, but Snyder doesn't seem to even admit it exists, let alone have the ability to walk it.

The argument can (and will) be made that Watchmen is just entertainment, and maybe that's a whole different essay. This isn't about violence in the media, however, but rather the direct subversion of a film's text by its presentation. Unless this is done intentionally, it just seems like bad filmmaking. Certainly the soundtrack plays like My First Mixtape, with no comprehension either that anyone has heard of Jimi Hendrix or Bob Dylan before or that just because a song is cool, it may not be appropriate for any given scene. This is minor compared to my other complaint, of course, but anyone who thinks that Leonard Cohen's “Hallelujah” is appropriate for the awkward sex it's set to is just not thinking. And all of this together weakens the impact the film ought to have. Watchmen should be entertaining, true. There should be violence and sex. But it shouldn't work against the idea that there is a moral contradictions inherent in the very activity of masked vigilantism.

There were things I liked about the film, but most of those were in the comic, too. I find the characters of Rorschach and Dr. Manhattan very compelling, and they were realized well enough by their actors (though I object to the fakey Batman voice of Rorschach—why would he have to disguise his voice if no one knows who he is?--and the bad computer rendering of many of Manhattan's facial expressions). Everyone on screen was, at the very least, very game. The one music cue I enjoyed was a Muzak version of “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” at an opportune moment, because it was both subtle and ridiculous. But the voyeuristic glee with which the violence was carried out worked against my enjoyment of the movie—call me a fuddy duddy, but I'd have appreciated it more if I could have sensed some condemnation behind, say, the graphic incineration of Vietnamese soldiers instead of an empty “look what we can do.” I do not get the sense that we're supposed to be horrified. Everything is so shiny, and at the same time so removed, that in the end I don't see how the film (with the help of others which have come before) can help but put us in some approximation of Dr. Manhattan's position: unable to relate to these figures as anything but effects, and only theoretically able to appreciate human life as we see it on screen. Read more!

I was not, however, prepared for the travesty director Zack Snyder made of it that I saw last night.

However ridiculous (and racist, and homophobic) I found Snyder's 300, most of what I objected to in the film was present in Frank Miller's comic. I didn't like how it looked, either, but shiny computer graphics and faster-than-the-eye-can-see fight sequence editing are something I live with nearly every time I see a modern Hollywood film, and I just sound more curmudgeonly and bitter every year. Watchmen had that, too, and I was prepared. What I was not prepared for was the sheer disconnectedness of the text and the presentation, which impressed itself upon me within minutes.

Is it a spoiler to say that the Zapruder film recreation nestled in the credits was one of the most tasteless things I have ever witnessed, JFK's assassination writ large upon an IMAX screen for the cheapest of shots at one of the main characters? The scene was presented with no more nor less fanfare than the recreation of the famous WWII photo of the sailor kissing the nurse, substituting Silhouette for the sailor (who we can see heading off another direction in the background). What's most astonishing to me is not so much the audacity of the decision as the filmmakers' apparent inability to see the difference between the two appropriations. Both have the same gleeful, detail-oriented “because we can” attitude about them, and even if our emotions are meant to be manipulated in slightly different directions, the intent of both is clearly to titillate.

This lack of thought permeates the entire film, from the soundtrack to the fight sequences. For a film that's about recreating a beloved comic in painstaking detail (when convenient or showy), it's astonishingly unaware of what the comic is about. One would hope, in other words, that the makers of a movie about the depravity of modern society would take some care not to directly contribute to same. Instead, we are simultaneously lectured about standing by and letting violence happen and shown endless slow-motion frames of compound fractures rendered in loving, hyper-real, computer-generated detail. It's pornography, and it's exactly the sort of thing Rorschach would be combating. I'm hardly holding him up as an example to be followed, and neither am I condemning pornography. But they don't belong together, and what is more, I cannot sense the tiniest bit of intelligence behind the decisions that went into the making of this film. There's a fine line between demonstrating your point and subverting it, but Snyder doesn't seem to even admit it exists, let alone have the ability to walk it.

The argument can (and will) be made that Watchmen is just entertainment, and maybe that's a whole different essay. This isn't about violence in the media, however, but rather the direct subversion of a film's text by its presentation. Unless this is done intentionally, it just seems like bad filmmaking. Certainly the soundtrack plays like My First Mixtape, with no comprehension either that anyone has heard of Jimi Hendrix or Bob Dylan before or that just because a song is cool, it may not be appropriate for any given scene. This is minor compared to my other complaint, of course, but anyone who thinks that Leonard Cohen's “Hallelujah” is appropriate for the awkward sex it's set to is just not thinking. And all of this together weakens the impact the film ought to have. Watchmen should be entertaining, true. There should be violence and sex. But it shouldn't work against the idea that there is a moral contradictions inherent in the very activity of masked vigilantism.

There were things I liked about the film, but most of those were in the comic, too. I find the characters of Rorschach and Dr. Manhattan very compelling, and they were realized well enough by their actors (though I object to the fakey Batman voice of Rorschach—why would he have to disguise his voice if no one knows who he is?--and the bad computer rendering of many of Manhattan's facial expressions). Everyone on screen was, at the very least, very game. The one music cue I enjoyed was a Muzak version of “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” at an opportune moment, because it was both subtle and ridiculous. But the voyeuristic glee with which the violence was carried out worked against my enjoyment of the movie—call me a fuddy duddy, but I'd have appreciated it more if I could have sensed some condemnation behind, say, the graphic incineration of Vietnamese soldiers instead of an empty “look what we can do.” I do not get the sense that we're supposed to be horrified. Everything is so shiny, and at the same time so removed, that in the end I don't see how the film (with the help of others which have come before) can help but put us in some approximation of Dr. Manhattan's position: unable to relate to these figures as anything but effects, and only theoretically able to appreciate human life as we see it on screen. Read more!

Bluebeard's Castle (1964)

The story of Bluebeard exists in several variations, but usually goes like this: a poor girl gets married off to an ugly (though rich) brute who tells her he can go anywhere in his house/mansion/castle but this one room, and that she must keep this key/egg with her at all times. By the way, he says, I'm going on a trip. The wife, driven by her womanly curiosity, enters the forbidden room to find a bloody abattoir filled with former Mrs. Bluebeards. She drops the key/egg, and to her dismay finds the blood will not wash off, thus alerting Bluebeard upon his return that she has gone against his orders.

This happens a few times until lucky number three, usually a sister of the other two, devises a clever plan to avoid dropping the key/egg or alert some sort of lover or brother of her predicament. This wife is rescued, and sometimes rescues the other wives, who can be sewed back together or pulled out of hell or otherwise recovered. The story is a flip-side of "Beauty and the Beast," where the vicious new husband really is a monster who cannot be redeemed, and where the woman's main attribute, curiosity, gets her into trouble. I suppose the lesson is that marriage is scary for a young girl, and sometimes the vicious beast turns out to be all right—and sometimes he doesn’t.

This basic storyline is more or less absent from Bartok’s opera Bluebeard’s Castle and Michael Powell’s 1963 film for German television. This film is very rare, and a few weeks ago I got the opportunity to see the one print that’s available. According to Powell’s wishes, the German opera is presented without translation, and only a few descriptive subtitles cue you in to certain emotions or events. (You can see the first 9 minutes here)

(click "Read More" for the rest, including slight spoilers for a film you probably won't see)

The experience is hard to describe. The film is an hour of visual interpretation of Bluebeard’s seven doors, the only action being that Bluebeard brings his new wife, Judith, home and informs her he has seven doors that she cannot look behind. The "public" part of his castle is filled with abstract sculptures of body parts; the first thing Judith says is that she’s going to bring happiness and light into it. She then proceeds to gain entry into each room, and the opera/movie follows a pattern in which Bluebeard denies her, then relents, she is fascinated by what she sees, and at length somewhat troubled. She keeps seeing blood. On the crown, on the clouds, marring the beauty of the things Bluebeard is showing her.

This, of course, is present in the opera itself, and what Powell’s film does is bring movie technique to a rather stagey production design. The film did not have a lot of money to work with, but what was achieved was a sort of synthesis of film and stage technique; everything we see could have been used on stage, but the camera allows Powell to play with time and point of view. The doors are sometimes represented by monoliths in a room, sometimes by transparent doors with little relation to any actual architecture. The flowers in the garden look to me like lighting gels. The basic unreality of the setting (and the lack of subtitles) allow for a multitude of interpretations; I don’t think anyone in the theater that night saw the same film. Why does Bluebeard show Judith the torture chamber and armory first, and with minimal reluctance, while the lake of tears takes significant prying? Are his wives, behind the last door, really dead? Or do they symbolize the memory of his past loves, as is suggested by his comparing them to dawn and midday? In the end, why can’t they be together? Was Judith too curious, or Bluebeard too reticent? Is any of this real, and if not, whose head are we in?

Unlike the original stories, Bluebeard does not leave his wife alone in the house as a sort of trick. He is present the entire time, and gives in to her demands to see each successive room. He is not a hideous monster—often interpreted in old illustrations as having "Eastern" features—but a strong-looking curly-haired man. It is not even clear whether there is any actual blood, or whether it is Judith’s imagination which coats Bluebeard’s inner life with it. But because the opera is called "Bluebeard’s Castle," anyone watching it with knowledge of the story is going to bring it to bear on what they’re seeing. This, for me, was one of the most interesting aspects of the thing. Because to me, most of it was happening not in real rooms but in the emotional lives of the protagonists. And to do Bluebeard without the dead wives, without the slaughterhouse, performed in large part on the marital bed, brings out so many new elements that I almost don’t know where to begin.

As we’ve seen in the trajectory of stories like Beauty and the Beast and Phantom, there is a movement from fear to sexualization of the Other. This is obviously far too simplistic a notion, but in general the Beast and the Phantom have become more acceptable partners, even in their inhumanity. Bartok/Powell’s Bluebeard does not seem like a monster at all, but a somewhat prickly man who presents a not inconsiderable sexual allure for his new wife. This interpretation seems to put the former bloodiness of the story down to anxiety over sexuality; without that anxiety, there is no need to warn the woman off the appetites of the husband. What was once threatening is now actually attractive. And the fact that Bluebeard can more easily show Judith his torture chamber and armory is in keeping with the abstract threat of the main chamber of his home. He is fine with this perception of him, and Judith is as well. These first rooms are his defenses as well as the basis of his masculine appeal, and it’s telling that he presents them before showing her the treasure and the gardens, and likewise telling that upon seeing the first rooms she only wants more. Of course in the end, she joins his other loves in the room of maybe-he-killed-them-and-maybe-he-didn’t, but the threat here seems more emotional than to life and limb.

And that may represent a very basic shift in society, in terms of what marriage means and what perils await most people in first world countries. It’s not that the original story assumed that many marriages ended in the husband hacking the wife up, but marriages were much more likely to be arranged without the consent of the girl, and life was a lot more difficult. In the early 20th century, when the opera was written, marriage was a choice, a little danger had become alluring, and the consequences were no longer the same.

Read more!

This happens a few times until lucky number three, usually a sister of the other two, devises a clever plan to avoid dropping the key/egg or alert some sort of lover or brother of her predicament. This wife is rescued, and sometimes rescues the other wives, who can be sewed back together or pulled out of hell or otherwise recovered. The story is a flip-side of "Beauty and the Beast," where the vicious new husband really is a monster who cannot be redeemed, and where the woman's main attribute, curiosity, gets her into trouble. I suppose the lesson is that marriage is scary for a young girl, and sometimes the vicious beast turns out to be all right—and sometimes he doesn’t.

This basic storyline is more or less absent from Bartok’s opera Bluebeard’s Castle and Michael Powell’s 1963 film for German television. This film is very rare, and a few weeks ago I got the opportunity to see the one print that’s available. According to Powell’s wishes, the German opera is presented without translation, and only a few descriptive subtitles cue you in to certain emotions or events. (You can see the first 9 minutes here)

(click "Read More" for the rest, including slight spoilers for a film you probably won't see)

The experience is hard to describe. The film is an hour of visual interpretation of Bluebeard’s seven doors, the only action being that Bluebeard brings his new wife, Judith, home and informs her he has seven doors that she cannot look behind. The "public" part of his castle is filled with abstract sculptures of body parts; the first thing Judith says is that she’s going to bring happiness and light into it. She then proceeds to gain entry into each room, and the opera/movie follows a pattern in which Bluebeard denies her, then relents, she is fascinated by what she sees, and at length somewhat troubled. She keeps seeing blood. On the crown, on the clouds, marring the beauty of the things Bluebeard is showing her.

This, of course, is present in the opera itself, and what Powell’s film does is bring movie technique to a rather stagey production design. The film did not have a lot of money to work with, but what was achieved was a sort of synthesis of film and stage technique; everything we see could have been used on stage, but the camera allows Powell to play with time and point of view. The doors are sometimes represented by monoliths in a room, sometimes by transparent doors with little relation to any actual architecture. The flowers in the garden look to me like lighting gels. The basic unreality of the setting (and the lack of subtitles) allow for a multitude of interpretations; I don’t think anyone in the theater that night saw the same film. Why does Bluebeard show Judith the torture chamber and armory first, and with minimal reluctance, while the lake of tears takes significant prying? Are his wives, behind the last door, really dead? Or do they symbolize the memory of his past loves, as is suggested by his comparing them to dawn and midday? In the end, why can’t they be together? Was Judith too curious, or Bluebeard too reticent? Is any of this real, and if not, whose head are we in?

Unlike the original stories, Bluebeard does not leave his wife alone in the house as a sort of trick. He is present the entire time, and gives in to her demands to see each successive room. He is not a hideous monster—often interpreted in old illustrations as having "Eastern" features—but a strong-looking curly-haired man. It is not even clear whether there is any actual blood, or whether it is Judith’s imagination which coats Bluebeard’s inner life with it. But because the opera is called "Bluebeard’s Castle," anyone watching it with knowledge of the story is going to bring it to bear on what they’re seeing. This, for me, was one of the most interesting aspects of the thing. Because to me, most of it was happening not in real rooms but in the emotional lives of the protagonists. And to do Bluebeard without the dead wives, without the slaughterhouse, performed in large part on the marital bed, brings out so many new elements that I almost don’t know where to begin.

As we’ve seen in the trajectory of stories like Beauty and the Beast and Phantom, there is a movement from fear to sexualization of the Other. This is obviously far too simplistic a notion, but in general the Beast and the Phantom have become more acceptable partners, even in their inhumanity. Bartok/Powell’s Bluebeard does not seem like a monster at all, but a somewhat prickly man who presents a not inconsiderable sexual allure for his new wife. This interpretation seems to put the former bloodiness of the story down to anxiety over sexuality; without that anxiety, there is no need to warn the woman off the appetites of the husband. What was once threatening is now actually attractive. And the fact that Bluebeard can more easily show Judith his torture chamber and armory is in keeping with the abstract threat of the main chamber of his home. He is fine with this perception of him, and Judith is as well. These first rooms are his defenses as well as the basis of his masculine appeal, and it’s telling that he presents them before showing her the treasure and the gardens, and likewise telling that upon seeing the first rooms she only wants more. Of course in the end, she joins his other loves in the room of maybe-he-killed-them-and-maybe-he-didn’t, but the threat here seems more emotional than to life and limb.

And that may represent a very basic shift in society, in terms of what marriage means and what perils await most people in first world countries. It’s not that the original story assumed that many marriages ended in the husband hacking the wife up, but marriages were much more likely to be arranged without the consent of the girl, and life was a lot more difficult. In the early 20th century, when the opera was written, marriage was a choice, a little danger had become alluring, and the consequences were no longer the same.

Read more!

Let the Right One In (2008)

[I'm trying something a little different with this one. There are spoilers for this film and Martin and some analysis if you hit "Read more" at the bottom of the post, but hopefully the part that shows bits will offer a decent review for those who wish it. Let me know how it works.]

Let the Right One In cuts right to the heart of this by making the vampire a pre-pubescent girl, it's almost a relief. Finally, a vampire film (with requisite gore) that is unflinchingly not about velvet-drenched sould-searching angst or eternal-youth rockstardom.

Instead, this Swedish film (based on a novel) is about a little boy, Oskar, who slowly befriends his new next-door neighbor, a strange, beautiful creature named Eli. Eli walks barefoot in the snow. Eli does not go to school. Eli lives with an older man who may or may not be related to her, but whose relationship is decidedly not parental. Oskar is bullied at school, and spends most of his time on his own, dreaming of revenge he never takes. As his relationship with Eli progresses, it becomes clear that neither of them really has anyone else, and the secret they share unites them in a world Oskar may or may not be ready to join.

The film is starkly real without sacrificing style (except for some dreadfully unfortunate CG cats I am endeavoring to forget about), and for the most part plays out like a boy-meets-girl story with periodic violence rending the silent, frozen landscape. The contrast here, both visually and thematically, is striking and effective, and it's probably the most interesting vampire movie I've ever seen.

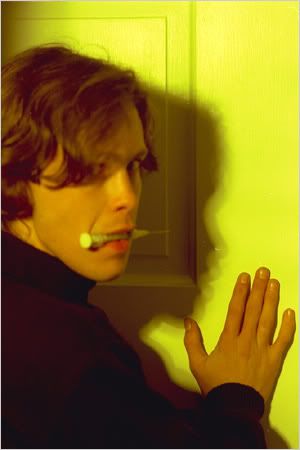

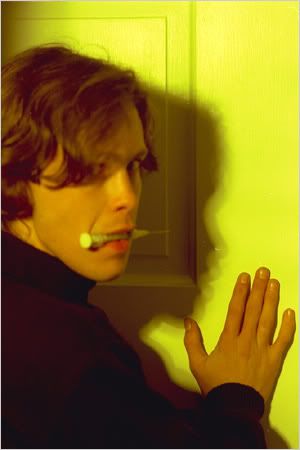

In many ways, while less subtly stylish, George Romero's Martin (1977) is the male companion piece to Let the Right One In. They're both about adolescence--the boy version naturally featuring an older protagonist. Martin's sexual anxiety manifests in a different way than Eli's, and his condition is ambiguous in a different way, and in the end the films are saying quite different things. But they both focus on individual (arrested) development, with vampirism as the diegetic cause of the arrest. What's unique about Martin's situation is that while he may or may not be a vampire, his reasons for thinking/pretending he is seem to be equal parts sexual (assuming his blood drinking falls into the "fetish" category) and a cry for attention (as exemplified by his anonymous late-night radio talk show calls). Martin makes the rape-fantasy aspect of the vampire myth explicit, and also explores the psychological hold the myth has on us for the simple reason that Martin is under its spell as well--whether or not he's a "real" vampire. Whatever that means.

In many ways, while less subtly stylish, George Romero's Martin (1977) is the male companion piece to Let the Right One In. They're both about adolescence--the boy version naturally featuring an older protagonist. Martin's sexual anxiety manifests in a different way than Eli's, and his condition is ambiguous in a different way, and in the end the films are saying quite different things. But they both focus on individual (arrested) development, with vampirism as the diegetic cause of the arrest. What's unique about Martin's situation is that while he may or may not be a vampire, his reasons for thinking/pretending he is seem to be equal parts sexual (assuming his blood drinking falls into the "fetish" category) and a cry for attention (as exemplified by his anonymous late-night radio talk show calls). Martin makes the rape-fantasy aspect of the vampire myth explicit, and also explores the psychological hold the myth has on us for the simple reason that Martin is under its spell as well--whether or not he's a "real" vampire. Whatever that means.

Eli, by contrast, is quite certainly a vampire, though the mythos has a few surprises for us (my favorite being the consequences of entering "uninvited," one of the most effective scenes in the film). And Eli's problem is not, as we've seen before (most explicitly in the film version of Interview with the Vampire and Kirsten Dunst's dolled-up Claudia), that she's a grown up stuck in a child's body. It's that she's eternally adolescent, even if her soul is old and has witnessed things we cannot even imagine.

Two models of vampiric adolescence

What's incredible about this, and what makes the explicitness of the vampire/puberty connection feel not at all overdone or cliched, is that Eli embodies qualities that could be explained by either her years of vampiric indifference to human life and gore or her developmental immaturity. She is like Oskar in her perceptions of right and wrong. Is it because her morality (that which we would call morality, anyway) has decayed, or because it never developed? She's caught eternally in the self-interest of childhood, though on the cusp enough to develop a strong attachment to a boy she sees herself in. It all seems so obvious when you think about it, but it doesn't play that way in the film, and it's refreshing to see the subject treated without kid gloves. The violence is never out of place--it's the reality of Eli's life, which is (not coincidentally) Oskar's fantasy.

Most arrested-development vampire fantasies capture the body at what many might consider its peak: the (sexually mature) teens or early twenties. For obvious reasons, since these are the sort of people we supposedly like to look at, and the stage at which we are told we should arrest our own aging process. Eli is beautiful, yes, but not the way a woman is. She moves a little awkwardly, very clearly still a girl though her prettiness makes this not a little disturbing, both in the pedophilic sense and a more thematic uncanniness. At the same time, her relationship with Oskar is troublesome in the sense that she is much, much older, but less troublesome than it might be because we get the sense that her mind as well as her body is caught at that stage. In a way, Eli can be made to represent not only our anxieties about our own pubescence and adulthood but that transition in others, and our culture's relationship to that body.

What's so compelling about Let the Right One In, along with the general quality of the filmmaking and acting, is that it doesn't shy away from any of these disturbing elements. Nor does it give us any clear answers. It creates a world, much like ours, where vampires are real but most people don't know about them, and then treats it from a child's point of view, with all the horror (and sweetness) that entails. The two children together are incredible, and the only reason I don't want to say that they transcend the words "vampire film" is because I think every horror movie should be saying something about our psychology or society. Perhaps most of them are, but few of them do so with the curious mix of overtness and restraint as this, and few offer so much food for thought. Read more!

Let the Right One In cuts right to the heart of this by making the vampire a pre-pubescent girl, it's almost a relief. Finally, a vampire film (with requisite gore) that is unflinchingly not about velvet-drenched sould-searching angst or eternal-youth rockstardom.

Instead, this Swedish film (based on a novel) is about a little boy, Oskar, who slowly befriends his new next-door neighbor, a strange, beautiful creature named Eli. Eli walks barefoot in the snow. Eli does not go to school. Eli lives with an older man who may or may not be related to her, but whose relationship is decidedly not parental. Oskar is bullied at school, and spends most of his time on his own, dreaming of revenge he never takes. As his relationship with Eli progresses, it becomes clear that neither of them really has anyone else, and the secret they share unites them in a world Oskar may or may not be ready to join.

The film is starkly real without sacrificing style (except for some dreadfully unfortunate CG cats I am endeavoring to forget about), and for the most part plays out like a boy-meets-girl story with periodic violence rending the silent, frozen landscape. The contrast here, both visually and thematically, is striking and effective, and it's probably the most interesting vampire movie I've ever seen.

In many ways, while less subtly stylish, George Romero's Martin (1977) is the male companion piece to Let the Right One In. They're both about adolescence--the boy version naturally featuring an older protagonist. Martin's sexual anxiety manifests in a different way than Eli's, and his condition is ambiguous in a different way, and in the end the films are saying quite different things. But they both focus on individual (arrested) development, with vampirism as the diegetic cause of the arrest. What's unique about Martin's situation is that while he may or may not be a vampire, his reasons for thinking/pretending he is seem to be equal parts sexual (assuming his blood drinking falls into the "fetish" category) and a cry for attention (as exemplified by his anonymous late-night radio talk show calls). Martin makes the rape-fantasy aspect of the vampire myth explicit, and also explores the psychological hold the myth has on us for the simple reason that Martin is under its spell as well--whether or not he's a "real" vampire. Whatever that means.

In many ways, while less subtly stylish, George Romero's Martin (1977) is the male companion piece to Let the Right One In. They're both about adolescence--the boy version naturally featuring an older protagonist. Martin's sexual anxiety manifests in a different way than Eli's, and his condition is ambiguous in a different way, and in the end the films are saying quite different things. But they both focus on individual (arrested) development, with vampirism as the diegetic cause of the arrest. What's unique about Martin's situation is that while he may or may not be a vampire, his reasons for thinking/pretending he is seem to be equal parts sexual (assuming his blood drinking falls into the "fetish" category) and a cry for attention (as exemplified by his anonymous late-night radio talk show calls). Martin makes the rape-fantasy aspect of the vampire myth explicit, and also explores the psychological hold the myth has on us for the simple reason that Martin is under its spell as well--whether or not he's a "real" vampire. Whatever that means.Eli, by contrast, is quite certainly a vampire, though the mythos has a few surprises for us (my favorite being the consequences of entering "uninvited," one of the most effective scenes in the film). And Eli's problem is not, as we've seen before (most explicitly in the film version of Interview with the Vampire and Kirsten Dunst's dolled-up Claudia), that she's a grown up stuck in a child's body. It's that she's eternally adolescent, even if her soul is old and has witnessed things we cannot even imagine.

What's incredible about this, and what makes the explicitness of the vampire/puberty connection feel not at all overdone or cliched, is that Eli embodies qualities that could be explained by either her years of vampiric indifference to human life and gore or her developmental immaturity. She is like Oskar in her perceptions of right and wrong. Is it because her morality (that which we would call morality, anyway) has decayed, or because it never developed? She's caught eternally in the self-interest of childhood, though on the cusp enough to develop a strong attachment to a boy she sees herself in. It all seems so obvious when you think about it, but it doesn't play that way in the film, and it's refreshing to see the subject treated without kid gloves. The violence is never out of place--it's the reality of Eli's life, which is (not coincidentally) Oskar's fantasy.

Most arrested-development vampire fantasies capture the body at what many might consider its peak: the (sexually mature) teens or early twenties. For obvious reasons, since these are the sort of people we supposedly like to look at, and the stage at which we are told we should arrest our own aging process. Eli is beautiful, yes, but not the way a woman is. She moves a little awkwardly, very clearly still a girl though her prettiness makes this not a little disturbing, both in the pedophilic sense and a more thematic uncanniness. At the same time, her relationship with Oskar is troublesome in the sense that she is much, much older, but less troublesome than it might be because we get the sense that her mind as well as her body is caught at that stage. In a way, Eli can be made to represent not only our anxieties about our own pubescence and adulthood but that transition in others, and our culture's relationship to that body.

What's so compelling about Let the Right One In, along with the general quality of the filmmaking and acting, is that it doesn't shy away from any of these disturbing elements. Nor does it give us any clear answers. It creates a world, much like ours, where vampires are real but most people don't know about them, and then treats it from a child's point of view, with all the horror (and sweetness) that entails. The two children together are incredible, and the only reason I don't want to say that they transcend the words "vampire film" is because I think every horror movie should be saying something about our psychology or society. Perhaps most of them are, but few of them do so with the curious mix of overtness and restraint as this, and few offer so much food for thought. Read more!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)